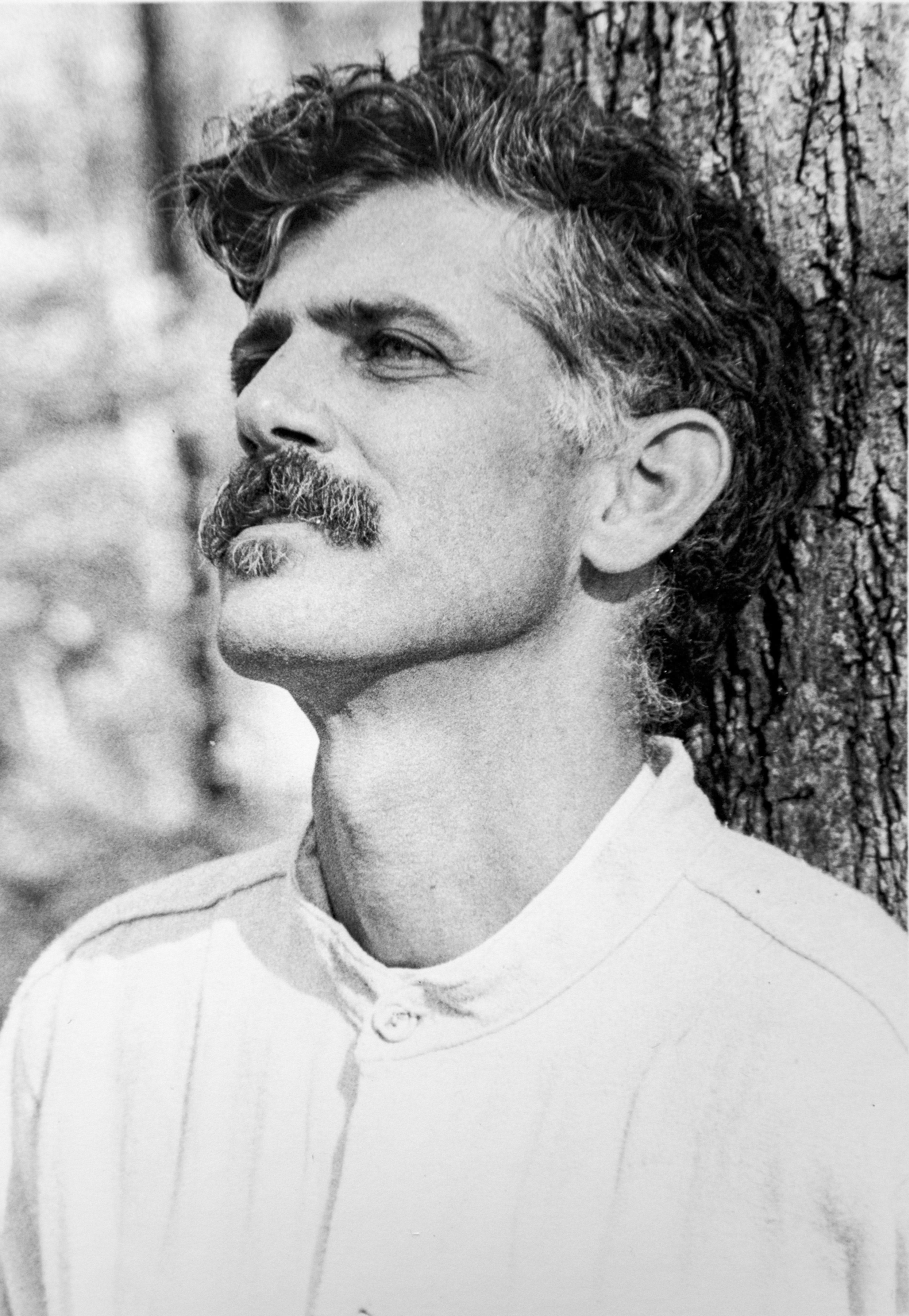

Andy Mahler, Folk Hero of the Forest

Andy Mahler has devoted more than 50 years of his life to protecting the forest. His legacy is the subject of a new book by environmental reporter Steven Higgs, Mahler’s long-time friend. LP’s Anne Kibbler shares Mahler’s reflections on life and explores Higgs’s dedication to honoring one of his her

A journey through the Hoosier National Forest with Andy Mahler is a spiritual quest, a melding of a mind deeply attuned to the environment with the physicality and majesty of the surrounding trees.

“It gives me great joy just to be in the presence of a tree that’s been around 300, maybe 400 years,” he says, pausing by a giant American beech. And, standing in a 200-year-old pioneer cemetery in the middle of the woods: “It’s a circle of trees holding the stones in a loving embrace.”

Mahler, 74, an activist, author, and musician, has devoted his life to the forest. Now, facing a terminal prognosis of stage 4 cancer, and a last fight to save yet another tract of woodland, he is the subject of an upcoming book chronicling his decades of advocacy.

At the same time, the book, Andy Mahler and the Hoosier National: An American Folk Hero and the Forest He Loved, represents a parallel odyssey for author Steven Higgs. It’s a culmination of 50 years of his own work photographing and writing about the forest, with Mahler as the focal point of this latest endeavor.

“This is the fulfillment of a life dream,” Higgs said of the book, noting he and Mahler are the same age. “Andy has always been a hero of mine. He’s larger than life to me.”

Higgs’s book recounts Mahler’s family history, his move to southern Indiana, his life philosophies and outlook on death (he’s not afraid), and his dedication to saving what he calls “the most beautiful temperate forest on earth.”

Raised in Bloomington, Mahler — a distant descendent of composer Gustav Mahler — is the son of groundbreaking biochemist Henry Mahler, a longtime faculty member at Indiana University, and Annemarie Ettinger, an artist. Both were born in Vienna, Austria, and emigrated to the United States to escape Nazi Europe.

Mahler refers to the Holocaust as a major disruption in his life.

“Not having a homeland changes your relationship with the past,” he said. “Not having an investment in the future of watching your kids turn into adults — I don’t have that. I have this.”

“This” is his life in the midst of rural Orange County, where he moved in 1979, and the homestead he set up with his wife, Linda Lee. Known as the Lazy Black Bear, the eclectic collection of dwellings and outbuildings sits in the middle of 270 acres of woodlands and has served for decades as a gathering place for forest champions and the couple’s many dear friends.

In the mid-1980s, Mahler and a group of like-minded activists founded Protect Our Woods, successfully fighting a U.S. Forest Service plan to clearcut, log, drill, and mine in the Hoosier National Forest. It was around this time that Mahler first crossed paths with Higgs, who was covering the issue as an environmental reporter at what was then the Bloomington Herald-Telephone.

At that point, Higgs had already been chronicling the forest independently for a good ten years, having fallen in love with it on a trip up Saddle Creek with a friend; pictures from his first photographic expedition there, in May 1975, are included in his book. From their initial meetings as reporter and source, Higgs and Mahler developed a deep friendship and mutual respect, crossing paths frequently in their shared quest to shed light on the beauty and vulnerability of the forest.

Higgs, who continued to report on environmental issues as the editor and publisher of the now-closed Bloomington Alternative, has taken thousands of photos of the Hoosier National and other wild areas of Indiana. He’s the author of three books published by Indiana University Press — guides to natural areas of southern and northern Indiana, and Eternal Vigilance: Nine Tales of Environmental Heroism in Indiana, published in 1994 and featuring Mahler and his efforts over the previous decade to save the forest. This latest book brings Mahler’s story to the present day.

Building on their victory with Protect Our Woods, Mahler and Lee had expanded their outreach throughout the Ohio Valley through an organization called Heartwood, advocating for the power of collective action and sharing their vision for the future of the forests in Indiana and surrounding states. Founded in 1991, Heartwood now encompasses almost 100 member organizations in 18 states, including Arkansas, Virginia, Michigan, and Mississippi.

More recently, after several years in retirement, Mahler answered the call back to action when encroachment on the forest hit his own back yard. In 2021, the U.S. Forest Service proposed clearcutting and burning a section of 30,000 acres called Buffalo Springs, saying such management would reintroduce native species, improve forest diversity, and make the area more resilient to climate change.

The project area, said the forest service, is experiencing “a steady decline in forest health.” An assessment of the project’s impact found the environment “will not be irreparably affected by the proposed actions.”

Mahler and others vehemently disagree.

Buffalo Springs butts up against Mahler’s land. It’s been slated for intense management practices, he explained during a tour with Higgs in early July, precisely because so few people live there.

But these wild woodland tracts are “the areas most deserving of protection with the least degree of oversight,” he said, contending the project would destroy trees and wildlife habitat, introduce gravel-covered roads, threaten the karst topography, and pollute the environment with herbicides and burnoff byproducts.

The woods are in a critical location, sitting at the headwaters of Patoka Lake, a water source for 100,000 people. Erosion from clearcutting, as well as runoff from the burning and clearing of land, would have a significant impact on both the forest and the lake, Mahler believes.

Indiana Gov. Mike Braun, a native of nearby Jasper, Indiana, is on his side. In February 2025, Braun wrote to the chief of the U.S. Forest Service, urging him to drop the Buffalo Springs project. Braun, a keen outdoorsman, expressed concern about the impact both on recreation and on the quality of Patoka Lake’s water. The conflict is gaining further attention through an upcoming documentary, Saving the Hoosier, which features Mahler prominently.

Since Braun’s intervention, the project has remained in limbo, and Mahler said no one knows what its status is.

As for his own condition, Mahler regards his mortality with a naturally philosophical mindset. He said he’s been questioning his existence since he was 11 years old: “What does it mean to be a living, caring human being at this point in history?”

His relationship with the forest has helped him answer that question. Mahler describes himself as “so ingrained in the land, it’s miraculous and revelatory on a daily basis.” He moved to the forest because, he said, “I wanted to be surrounded by beauty and kindness … the natural world was part of an ongoing legacy of self-identification.”

And, he said, his prognosis also has helped him discover his purpose. When he heard his diagnosis, he told Higgs, he resolved to yield to his body “ideally painlessly and in ways that allow for those near and dear to me to be able to fill the empty places.” But after his friends’ overwhelming response to the announcement of his news, he decided to live out his days with as much gusto as he could summon.

“I’m determined to honor that love that’s been shown to me,” he told Higgs.

And what’s it like to be the subject of a book, for someone who has authored many pieces of his own?

“I’m hoping it will reach some confused kid who’ll find this set of words and say, ‘Oh my goodness, I’m not alone,’” he said.

Mahler is also the subject of some late-in-life honors. In 2024, the California-based nonprofit Fund for Wild Nature named him Grassroots Activist of the Year. And the Indiana Democratic Party, at its August 2025 gathering in French Lick, will present him with the Legacy Award for his outstanding contributions to the party as a poll worker, candidate for commissioner, and active citizen at numerous county and state meetings.

Higgs, his biographer and friend for the last 40 years, will introduce him, along with the first copies of the book that celebrates the weaving together of their shared dedication to the forest.

“This could be career-defining for both of us, and that’s what I hope it’s going to be,” Higgs said.

Editor’s note: Andy Mahler passed away on August 30, 2025. He was 74.

A life dream fulfilled

Andy Mahler and the Hoosier National: An American Folk Hero and the Forest He Loved will be available at stevenhiggs.com. All proceeds beyond printing, shipping, and handling will be donated toward nonprofit organizations fighting for the Hoosier National and other of our nation’s imperiled national forests.